Content from Introduction to the LaTeX Workflow

Last updated on 2025-07-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 12 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What do I need to do to write and edit a LaTeX document?

- How can I render a LaTeX document?

Objectives

- Demonstrate how to create a new LaTeX Document.

- Become familiar with the TeXworks interface.

- Compile a LaTeX document with the TeXworks editor.

- Compile a LaTeX document with the command line.

What is LaTeX

LaTeX is a typesetting language, useful for combining text with mathematical equations, figures, tables, and citations, among other things.

Unlike common word processors like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer, LaTex is a markup language, meaning that formatting (including bold text, bullet points, and changes in font size) is indicated by the use of commands, special characters, or environments.

In order to produce the actual document, this mark-up text must be compiled. Errors in the mark-up can either be non-fatal, meaning the document will compile with some warnings; or fatal, meaning the document will fail to compile.

Our First LaTeX Document

To begin with, we will create a new directory to hold our files for

this workshop. Call it latex-workshop, and make a note of

the path to this directory.

Start the TeXworks editor and immediately “save” the file. This will

prompt you for a location to save the file, so navigate to the

latex-workshop directory you just created, and save the

file as main.tex.

The TeXworks Interface

The TeXworks interface is divided into three main sections: - The Editor: This is where you write your LaTeX code. It supports syntax highlighting and basic code completion. - The Preview Pane: This shows the compiled output of your LaTeX code. This window will appear whenever we compile the document. - The Menu Bar: This contains various options for managing your document, such as saving, compiling, and printing. You can also access the preferences and settings from here.

The overall interface is designed to be simple and intuitive, focusing on the essential features of a LaTeX editor. Note the large green triangle button in the top left corner of the interface. This is the “Typeset” button, which compiles your LaTeX document and updates the preview pane with the rendered output. Next to the “Typeset” button is a drop-down menu that allows you to select the typesetting engine you wish to use. For this workshop, we will use the default engine, PDFLaTeX.

Compiling a LaTeX Document

Type the following code into the editor:

Now click the green “Typeset” button in the top left corner of the interface. This will compile the document and update the preview pane with the rendered output. You should see a PDF preview of the document with the text “Hello, LaTeX!”.

When you click the “Typeset” button, TeXworks will run the PDFLaTeX compiler on your document. You will see a window appear on the bottom of the interface called “Console output”. This window contains the output of the compiler, including any warnings or errors that may have occurred during the compilation process. We will talk about this in more detail in a later episode.

Compiling a LaTeX Document from the Command Line

The TeXworks editor is a convenient way to write and compile LaTeX documents, but you are not limited to using it. Any program that can edit text files can be used to write LaTeX, which we can then compile from the command line.

You can use any text editor to write your LaTeX code. Some popular text editors for LaTeX include:

-

Visual Studio

Code

-

Emacs

-

Vim

- Notepad++ (Windows only)

We will continue to demonstrate with TeXworks, but you can use any text editor you prefer.

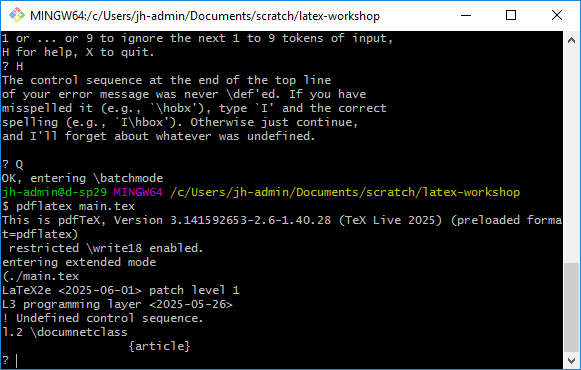

To compile a LaTeX document from the command line, you can use the

pdflatex command. Open a console or terminal window, then

navigate to the directory where you saved your main.tex

file.

Useful commands for navigating the command line:

-

cd <directory>: Change directory to<directory>.

-

ls(Linux/macOS) ordir(Windows): List the files in the current directory.

-

pwd(Linux/macOS): Print the current working directory.

Once you are in the correct directory, run the following command:

You should see output similar to the following:

This is pdfTeX, Version 3.141592653-2.6-1.40.28 (TeX Live 2025) (preloaded format=pdflatex)

restricted \write18 enabled.

entering extended mode

(./main.tex

LaTeX2e <2024-11-01> patch level 2

L3 programming layer <2025-04-29>

(e:/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/article.cls

Document Class: article 2024/06/29 v1.4n Standard LaTeX document class

(e:/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/size10.clo))

(e:/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/l3backend/l3backend-pdftex.def)

(./main.aux)

[1{e:/texlive/2025/texmf-var/fonts/map/pdftex/updmap/pdftex.map}] (./main.aux)

)<e:/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/fonts/type1/public/amsfonts/cm/cmr10.pfb><e:/texli

ve/2025/texmf-dist/fonts/type1/public/amsfonts/cm/cmr7.pfb>

Output written on main.pdf (1 page, 21048 bytes).

Transcript written on main.log.You can also use the compiler LuaLaTeX which is more powerful but might take a little bit longer to generate the pdf.

The output is this:

This is LuaHBTeX, Version 1.22.0 (TeX Live 2025)

restricted system commands enabled.

(./main.tex

LaTeX2e <2025-06-01> patch level 1

L3 programming layer <2025-07-11>

(/usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/article.cls

Document Class: article 2025/01/22 v1.4n Standard LaTeX document class

(/usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/size10.clo))

(/usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/tex/latex/l3backend/l3backend-luatex.def)

No file main.aux.

[1{/usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-var/fonts/map/pdftex/updmap/pdftex.map}]

(./main.aux))

406 words of node memory still in use:

3 hlist, 1 vlist, 1 rule, 2 glue, 3 kern, 1 glyph, 4 attribute, 48 glue_spec

, 4 attribute_list, 1 write nodes

avail lists: 2:38,3:4,4:1,5:26,6:2,7:56,9:24

</usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/fonts/opentype/public/lm/lmroman7-regular.o

tf></usr/local/texlive/2025/texmf-dist/fonts/opentype/public/lm/lmroman10-regul

ar.otf>

Output written on main.pdf (1 page, 4850 bytes).

Transcript written on main.log.Notice how the size of the pdf is about one forth when compiling with LuaLaTeX compared to pdflatex.

In the directory where you ran the command, you should now see a new

file called main.pdf, as well as some other files that were

created during the compilation process. The main.pdf file

is the rendered output of your LaTeX document, and you can open it with

any PDF viewer to see the result.

When you looked in your directory, you may have noticed that several

other files were created in addition to the main.pdf file.

These files are:

-

main.aux: This file contains auxiliary information used by LaTeX during the compilation process, such as cross-references and citations. -

main.log: This file contains the log output of the LaTeX compiler, including any warnings or errors that occurred during the compilation process.

The main.aux file is not something we really need to

worry about at this point, but the main.log file can be

useful for debugging if you encounter any issues with your LaTeX

document. We’ll take a closer look at the log file in a later

episode.

Challenge 1: NEED A NEW CHALLENGE

Challenge 3: NEED A NEW CHALLENGE

- We can use the TeXworks editor to write and compile LaTeX documents.

- The TeXworks interface is divided into three main sections: the editor, the preview pane, and the menu bar.

- We can compile a LaTeX document by clicking the “Typeset” button in the TeXworks editor.

- We can also compile a LaTeX document from the command line using the

pdflatexorlualatexcommand.

Content from File Structure

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is the basic structure of a LaTeX document?

- How do I see what my LaTeX document looks like when it’s rendered?

Objectives

- Become familiar with the basic structure of a LaTeX document.

- Use TeXworks to render a LaTeX document into a PDF.

- Identify how to add special characters to a LaTeX document.

Editing the Document

We can edit the main.tex file with TeXworks (or any text

editor of your choice). Let’s start by creating a simple LaTeX

document:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

\end{document}Errors happen! Check that you have entered each line in the text file exactly as written above. Sometimes seemingly small input changes give large changes in the result, including causing a document to not work. If you are stuck, try erasing the document and copying it fresh from the lines above.

Looking at our document

Our first document shows us the basics. LaTeX documents are a mixture of text and commands.

-

Commands start with a backslash

\and sometimes have arguments in curly braces{}. - Text is what you want to appear in the document and requires no special formatting.

Let’s look at the commands we’ve used so far:

-

\documentclass{article}: This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating. (We might also use this command to instruct LaTeX to use a specific font size, paper size, or other document settings - more on this later!) -

\begin{document}and\end{document}: These commands mark the beginning and end of the document body. These commands are required in every LaTeX document and create the document body.

You can have multiple \begin{...} and

\end{...} pairs in a single LaTeX document, but you must

have exactly as many \begin{...} commands as

\end{...} commands.

Everything before the \begin{document} command is called

the preamble. The preamble is where you set up the document,

including the document class, title, author, and any other settings you

want to apply to the entire document.

Comments

We can add comments to our document by using the %

character. Anything after the % on a line is ignored by

LaTeX. As in any other programming language, comments are useful for

explaining what the code is doing. We’ll start incorporating comments

into our document going forward to explain some of the specifics of the

LaTeX code we’re writing.

As we go, you should use your version of the document to add your own comments as a way of taking notes on what you’re learning, and to act as a reference for yourself in the future!

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

\end{document}Note that the comments are displayed in a different color in the text editor. This is called “syntax highlighting”. Not all text editors will do this by default, but you can often add syntax highlighting to your text editor of choice.

Going forward, the examples we provide will not always include comments, but you should add them to your document as you see fit.

Rendering the Document

As with our example from the previous episode, we can render our

document by clicking on the large green “Typeset” button in TeXworks, or

by running the command pdflatex main.tex in our

terminal/consoloe.

When running the command in the terminal, make sure you have saved your document first, as the command will only render the last saved version of the document.

Paragraphs

Note that we have an empty line between our two lines of text. This is important in LaTeX, as this indicates a new paragraph. Let’s try removing the empty line and recompiling the document to see what happens.

You should see that the two lines of text are now displayed on the

same line. This is because LaTeX treats the two lines as part of the

same paragraph. If you want to start a new paragraph, you need to leave

a blank line between the two paragraphs. Instead of using an empty line,

there is also the command \par that leads you to the same

result of creating a new paragraph. More on this in one of the

challenges below.

Special Characters

You’ve probably noticed by now that the characters \,

{, and } are special characters in LaTeX.

There are others though, such as $, %,

&, # and ^. These characters

tend to be much less common in text, but you can use them by “escaping”

them with a backslash. For example,

-

\%produces% -

\&produces& -

\#produces# -

\^produces^

and so on.

What about the \ character?

The \ character is used to escape other characters in

latex, so it’s not possible to escape it in the same way. Instead, you

can use \textbackslash to produce a backslash in your

document.

Sometimes, special characters can, unintentionally, conflate with

characters that are used after that special character. You can prevent

that by typing {} directly behind your special character.

The following LaTeX code gives you an example:

Challenges

Challenge 1: What’s wrong with this document?

There is an error in the following LaTeX document. Can you find it?

(Feel to make a main.tex file in a new project folder to test this out!)

Each section of a LaTeX document must be enclosed in a pair of

\begin{...} and \end{...}. This document is

missing the \begin{document} command.

Challenge 2: Displaying Special characters.

How would I display the following text in a LaTeX document?

5 is greater than 3 & 2 is less than 4. This is 100% true.Challenge 3: Paragraphs with

\par.

In the section about Paragraphs from above we learned that empty

lines are important to create paragraphs. However, there is also a LaTeX

command called \par which might be of help for us. Consider

the LaTeX code below. Can you already guess which of these options

prints Hello World! and This is my first LaTeX

document. in two separate lines? (Feel to make a main.tex file in a

new project folder to test this out!)

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

% Option A

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

% Option B

Hello World! This is my first LaTeX document.

% Option C

Hello World! \par This is my first LaTeX document.

% Option D

Hello World! \par

This is my first LaTeX document.

\end{document}The command \par initiates a new paragraph for us even

if we write text in just one line (see Option C). Solely, Option B out

of all four options does not create the intended new paragraph as

neither an empty line nor \par is used. Moreover, Option D

gives us the same result as Option A and Option C, although we used

both, \par and an empty line.

Challenge 4: One line of code with paragraphs and special characters.

How would I display the following text in a LaTeX document but using just one line of code?

Hello World! This is my first LaTeX document.

Now, I know how to initiate paragraphs without an empty line.

Even more, I can write # and ^ correctly using LaTeX.We need to use \par to initiate a new paragraph without

using a new line of code. Moreover, we need to use escapes before each

of the special characters. The following LaTeX code will display the

text correctly:

- The

%character is used to add comments to a LaTeX document. - LaTeX documents are a mixture of text and commands.

- Commands start with a backslash

\and sometimes have arguments in curly braces{}. - We can view errors by either clicking on the “Logs and output files” or hovering over the red circle in the text editor.

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like:

Content from Error Handling

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 15 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What do I do when I get an error message?

Objectives

- Understand how to interpret error messages in LaTeX

- Learn how to fix common errors in LaTeX documents

Error Handling

Error messages in LaTeX can often be difficult to understand, especially if you’re new to the language. However there are a few common errors that we can learn to recognize and fix, and a few techniques we can use to debug our documents based on the error messages we receive.

Inevitably, everyone makes mistakes when writing LaTeX documents. When you recompile your document, you might not see any changes in the preview pane. This could be because there is an error in your document. If there is an error, you will see a red number next to the “Recompile” button over the “Logs and output files” button. You will also see certain lines highlighted in red in the text editor, along with a suggestion of what the error might be.

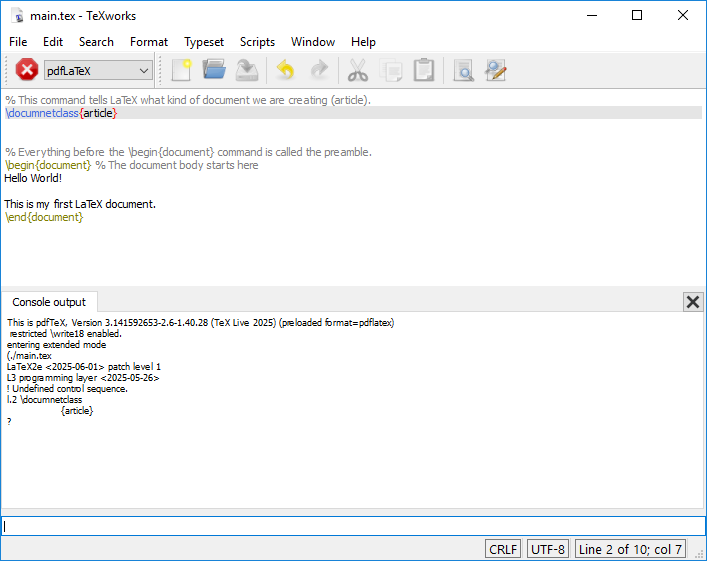

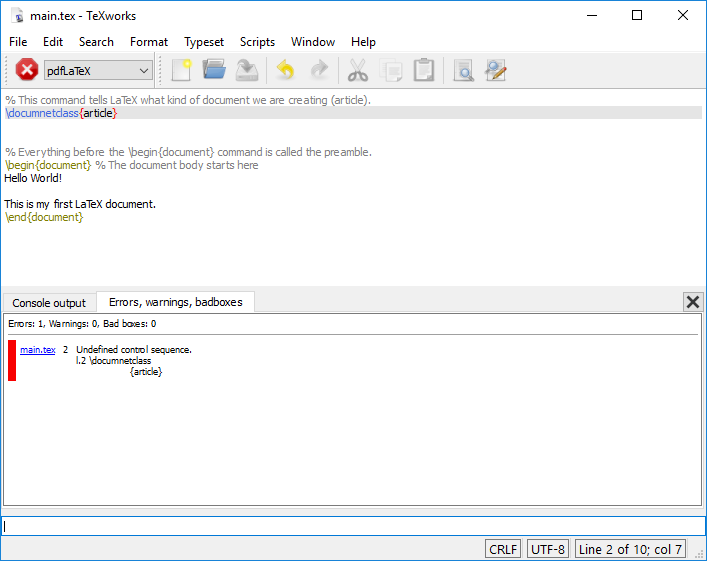

Let’s introduce an error into our project to see what this might look

like. Let’s introduce a typo into the documentclass command

by changing it to documnetclass. When we recompile the

document, we can see our errors:

LATEX

% This command is misspelled on purpose to generate an error

\documnetclass{article}

\begin{document}

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

\end{document}Commands in the console:

- Type

to proceed, - S to scroll future error messages,

- R to run without stopping

- Q to run quietly,

- I to insert something

- E to edit your file

- 1 or … or 9 to ignore the next 1 to 9 tokens of input,

- H for help

- X to quit

Fixing Errors

In general, the first error message you see is the most important one

to fix. In this case, all of the subsequent errors are related to the

initial error, which is that the \documentclass command is

undefined. Once we fix the typo in the \documentclass

command, the document will compile successfully.

The subsequent errors, talking about “missing begin document”, and “font size command not defined” are all cascading errors from the initial error. When LaTeX encounters an error, it can’t continue to compile the document, so it stops and reports the error it found. This can sometimes lead to multiple error messages, but generally it’s important to fix the first error first, as this will often resolve subsequent errors.

Anatomy of an Error Message

Let’s take a closer look at one of them and see what it tells us.

! Undefined control sequence.

l.2 \documnetclass

{article}This message tells us a few things: 1.

! Undefined control sequence.: This indicates that LaTeX

encountered a command that it doesn’t recognize. In this case, it’s the

misspelled \documnetclass command. 2. l.2:

This tells us that the error occurred on line 2 of the document. 3.

\documnetclass: This is the command that caused the error.

LaTeX doesn’t recognize this command because it is misspelled.

Of course, we know what the error was, so we can just fix it by

changing \documnetclass back to

\documentclass.

In general, the first error message in the list is the most useful one to look at. The other error messages are often just a result of the first error cascading down the document, so fixing the first one will often fix the rest of them too.

Common Errors

Let’s take a look at some common errors you might encounter when working with LaTeX.

Unidentified Control Sequence

We saw this one in our first example, but it can happen any where there is a command that LaTeX doesn’t recognize. This can happen if you misspell a command, or if you forget to include a package that defines the command, of if you try to use an incorrect command.

Here’s a quick example of this error:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

My Amazing Content: $\alpha = \fraction{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}$

\end{document}Attempting to compile this document results in the following error message:

! Undefined control sequence.

l.5 My Amazing Content: $\alpha = \fraction

{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}$So, again, we see that the error is an “Undefined control sequence”,

and it tells us that something in line 5 is not defined. In this case,

the command \fraction is not a valid LaTeX command.

File Not Found

Here’s another LaTeX excerpt:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{booktab}

\begin{document}

More Amazing Content!

\end{document}The following error message appears when you try to compile this document:

! LaTeX Error: File `booktab.sty' not found.This error indicates that LaTeX is unable to find the

booktab package. The correct package name should be

booktabs.

Overfull Boxes

The following code generates a warning message:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{graphicx}

\begin{document}

\section{Adding a rotated image}

We can rotate an image by setting the "angle" parameter:

\includegraphics[scale=2, angle=45]{example-image}

\end{document}The document compiles successfully, but there was some text that briefly appeared in the console output. Let’s look at the .log file to see what it says:

Overfull \hbox (390.7431pt too wide) in paragraph at lines 10--11

[][]

[]

[1

{c:/texlive/2025/texmf-var/fonts/map/pdftex/updmap/pdftex.map}]

Overfull \vbox (170.7431pt too high) has occurred while \output is active []

[2 <./example-image.png>] (./main.aux)This message indicates that there is an “overfull hbox” and “overfull vbox”. This means that the text or image is too wide or too tall for the page, and it is overflowing into the margins. This is a common issue when including images in LaTeX.

Errors vs Warnings vs Information

Not all messages are equal! LaTeX has three different types of messages:

-

Error: This is a serious issue that will prevent your document from compiling. You need to fix this before you can continue. -

Warning: This is a less serious issue that may not prevent your document from compiling, but it may cause issues with the output. You should still try to fix this, but it may not be critical. -

Information: This is just a message that provides additional information about the document. You can usually ignore this.

In Overleaf, error messages are shown in red, warnings are shown in yellow, and information messages in blue.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Why do I get this warning?

PLACEHOLDER

PLACEHOLDER

- Errors are common! Don’t be discouraged by them.

- The first error message is usually the most important one to fix.

- Read the error messages carefully, they often tell you exactly what the problem is.

Content from The Structure of a Document

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How are LaTeX documents structured?

Objectives

- Identify the different kinds of section commands in LaTeX.

- Create a list within a LaTeX document.

Sections

In a word processor, you might use headings to organize your document.In LaTeX, we’ll use the section commands:

\section{...}\subsection{...}

LaTeX will handle all of the numbering, formatting, vertical spacing, fonts, and so on in order to keep these elements consistent throughout your document. Let’s add sections to our document.

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

% The section command automatically numbers and formats the section heading.

\section{Sections}

I can add content to my first section!

% The subsection command does the same thing, but for sections within sections.

\subsection{Subsection}

I can put a subsection inside my first section.

\section{Second Section}

And this text will go into another section.

\end{document}You should have something that looks like this:

There are many different section commands in LaTeX, including

\subsubsection{...}, \paragraph{...},

\chapter{...}, and more. Each of these commands will create

a new section heading with a different level of indentation and

numbering.

Some of these commands are only available in certain document classes, so be sure to check the documentation for the class you are using.

Lists

In LaTeX, as in markdown, there are two types of lists: ordered and

unordered. They are both defined with \begin{...} and

\end{...} commands, as we saw with the document body. Let’s

add an ordered list to our document.

We’ll replace our “Second Section” with one for “Lists” and add an ordered list:

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

% The section command automatically numbers and formats the section heading.

\section{Sections}

I can add content to my first section!

% The subsection command does the same thing, but for sections within sections.

\subsection{Subsection}

I can put a subsection inside my first section.

\section{Lists}

There are two types of lists: ordered and unordered.

\subsection{Ordered}

Ordered lists have a number or letter associated with each item.

\begin{enumerate}

\item Item 1

\item Item 2

\item Item 3

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}When you compile this document, you should see something like this in the preview pane:

Note that the \item commands do not need to be enclosed

in braces. These commands do not take any arguments, so they can be used

as standalone commands. The text that follows the \item

command will be treated as the content of the list item. However, you

are able to specify your own bullet point symbols with

\item[] manually. For instance, if you want a list with

small letters in brackets you can use the following LaTeX code:

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

% List with custom bullet point symbols

\begin{itemize}

\item[(a)] Item 1

\item[(b)] Item 2

\item[(c)] Item 3

\end{itemize}

\end{document}It’s also possible to create a list with roman numerals automatically

with the enumitem package:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{enumitem} %<-- package for lists https://texdoc.org/serve/enumitem/

% \setlist{label=\Roman*} %<-- globally defining the enumeration system

\begin{document}

\begin{enumerate}[

label=\emph{\roman*}), %<-- change labeling system locally (or \Roman)

leftmargin=5cm, %<-- change indent on the left

]

\item First

\item Second

\item Third

\item Fourth

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}Adding an unordered list is just as easy. We can use the exact same

syntax, but replace the enumerate environment with

itemize.

LATEX

% This command tells LaTeX what kind of document we are creating (article).

\documentclass{article}

% Everything before the \begin{document} command is called the preamble.

\begin{document} % The document body starts here

Hello World!

This is my first LaTeX document.

% The section command automatically numbers and formats the section heading.

\section{Sections}

I can add content to my first section!

% The subsection command does the same thing, but for sections within sections.

\subsection{Subsection}

I can put a subsection inside my first section.

\section{Lists}

There are two types of lists: ordered and unordered.

\subsection{Ordered}

Ordered lists do not have numbers or letters associated with each item.

\begin{enumerate}

\item Item 1

\item Item 2

\item Item 3

\end{enumerate}

\subsection{Unordered}

Unordered lists are just a series of items preceded by a marker.

\begin{itemize}

\item Item 1

\item Item 2

\item Item 3

\end{itemize}

\end{document}Challenges

Challenge 1: What needs to change?

Challenge 2: Can you do it?

We would like to have the following appear in our LaTeX document:

- Apples

- Gala

- Fuji

- Granny Smith

- Bananas

- Oranges

How would you write this in LaTeX?

Challenge 3: Enumerate your list manually

We would like to have the following appear in our LaTeX document:

- Gala

- Fuji

- Granny Smith

How would you write this in LaTeX without using

enumerate but itemize with

\item[]?

- LaTeX documents are structured using section commands.

- There are many different section commands in LaTeX, including

\subsubsection{...},\paragraph{...},\chapter{...}, and more. - Lists in LaTeX are created using the

enumerateanditemizeenvironments.

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like.

Content from Using Document Classes

Last updated on 2025-07-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is a LaTeX Document class?

- How does a document class affect the layout of a LaTeX document?

Objectives

- Identify the various types of document classes available in LaTeX

- Create a document using an alternative document class

What is a Document Class?

A document class sets up the general layout of the document, including (but not limited to):

- design (margins, fonts, spacing, etc)

- availability of chapters

- title page layout

Document classes can also add new commands and environments to the document.

Document classes can also set global options that apply to the document as a whole.

These options are set in square brackets after the document class name, for example:

But we can add other parameters to this command to change the overall layout of the document. For example, we can set the size of the document to A4 paper by using:

We can also change the entire document to a two-column layout by using:

And we can of course combine these options:

The Base Document Classes

LaTeX comes with a set of standard document classes:

-

article: a short document without chapters -

report: a longer document with chapters, intended for single sided printing -

book: a longer document with chapters, intended for double sided printing, as well as other features like front and back matter -

letter: a short document with no sections -

slides: a document for creating slide presentations

We’re going to leave our main.tex file for a minute and

play around with some of these document classes.

Writing a Letter

So far we’ve been using the article document class.

Let’s try using the letter document class to write a

letter.

We’ve been working in “main.tex” so far, but we can create as many files in this project as we want. Let’s create a new file called “letter.tex” and write our letter there.

LATEX

\documentclass{letter}

\begin{document}

\begin{letter}{Some Address\\Some Street\\Some City}

\opening{Dear Sir or Madam,}

The text goes Here

\closing{Yours,}

\end{letter}

\end{document}Note the \\ used to create line breaks in the address -

we’ll get back to line breaking in a bit.

Creating a Presentation

Base LaTeX comes with the slides document class, which

is a very simple class for creating slide presentations. This class is

very basic and doesn’t have many features, but a more modern

implementation of a presentation class is beamer.

The beamer document class is text based, and so doesn’t

have the same level of interactivity as modern presentation software

like PowerPoint or Google Slides. However, being text-based does allow

the usage of version control systems like Git to track changes in the

presentation, and it can be compiled to PDF for easy sharing.

Let’s create a simple presentation using the beamer

document class. Start another new document called “slides.tex”.

LATEX

\documentclass{beamer}

\begin{document}

\begin{frame}

The beamer document class is a good starting point for creating a presentation.

\end{frame}

\begin{frame}

Being entirely text-based, it's not as powerful or user-friendly as modern presentation software.

\end{frame}

\end{document}When you compile this document, you should end up with a document that has two pages, each with the text of each slide centered in the middle of the page.

Function-rich Classes

The core classes included with base LaTeX are very stable, but this means they are also somewhat conservative in terms of features. Over time, third parties have developed a number of more powerful classes that add new features and functionality to LaTeX documents.

These include:

-

amsbook,amsart, andamsproc: classes for documents that use the American Mathematical Society’s style -

beamer: a class for creating slide presentations -

KOMA-Script: a set of classes that provide a more modern look and feel to LaTeX documents by providing parallel classes to the base classes (scrbook,scrartcl). -

memoir: a class that provides a lot of functionality for creating books, reports, and articles

These classes have a lot of customization options that can be used to alter the appearance of the document to exactly match your needs. We’ll explore how to figure out how to use these classes in a later episode.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Which don’t belong?

Which of the following are not a standard LaTeX document class?

articlereportbookletterpresentationmemoir

presentation is not a standard LaTeX document class -

the correct class is slides. Also memoir is

not a standard LaTeX document class, but a third-party class.

Challenge 2: What happens?

Suppose we have the following LaTeX slide presentation, but we want to turn it into an article. We can change the document class from “slides” to “article”, but what happens? And why?

LATEX

\documentclass{slides}

\begin{document}

\begin{slide}

Apples are an edible fruit produced by an apple tree. The tree originated in Central Asia, but

has since been introduced to many other regions.

\end{slide}

\begin{slide}

Some popular apple varieties include:

\begin{itemize}

\item Gala

\item Fuji

\item Golden Delicious

\end{itemize}

\end{slide}

\end{document}We can change the document class from “slides” to “article”, but the

slide environment does not exist in the

article document class. We end up with errors when we try

to compile the document, complaining that the slide

environment is not defined. We need to change the slide

environments to sections or subsections to

maintain the structure of the document:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

\section{Apples}

Apples are an edible fruit produced by an apple tree. The tree originated in Central Asia, but

has since been introduced to many other regions.

\subsection{Popular Apple Varieties}

Some popular apple varieties include:

\begin{itemize}

\item Gala

\item Fuji

\item Golden Delicious

\end{itemize}

\end{document}Challenge 3: Make your own beamer slides

Consider the following minimal example of an initial

beamer presentation. Let’s create a new file called

“beamer.tex” and copy the following code as a template into it:

LATEX

\documentclass{beamer}

%Information to be included in the title page:

\title{Sample title}

\author{Anonymous}

\institute{My Institution}

\date{2021}

\begin{document}

\frame{\titlepage}

\begin{frame}

\frametitle{Sample frame title}

This is some text in the first frame. This is some text in the first frame. This is some text in

the first frame.

\end{frame}

\end{document}Adapt these slides in the following way:

- Change the title to “LaTeX Workshop”

- Change the name of the author to your name.

- Change the institution name to “ABCD Project Group”.

- Change the date to “2025”.

- Change the frame title of the first slide after the title page to “What I have learned in this episode” and replace the example text on the slide with your key takeaway from this section.

- Besides the title page and the slide after the title page, create a third slide with the title “What I learned in the previous episodes”.

- Add an unordered list as content to this slide and describe in three bullet points your key takeaways from the previous episodes.

LATEX

\documentclass{beamer}

%Information to be included in the title page:

\title{LaTeX Workshop}

\author{My Name}

\institute{ABCD Project Group}

\date{2025}

\begin{document}

\frame{\titlepage}

\begin{frame}

\frametitle{What I have learned in this episode}

My key takeaway from this episode.

\end{frame}

\begin{frame}

\frametitle{What I learned in the previous episodes}

\begin{itemize}

\item Key learning 1

\item Key learning 2

\item Key learning 3

\end{itemize}

\end{frame}

\end{document}- LaTeX document classes set the general layout of the document

- The base document classes are

article,report,book,letter, andslides - Third-party classes can provide additional features

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like.

Content from Extending LaTeX

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I extend LaTeX to suit my needs?

- How can I define my own commands in LaTeX?

Objectives

- Demonstrate how to extend LaTeX using packages.

- Add custom commands to a LaTeX document.

Adding Packages

After we’ve declared a class, we can use the preamble section of our document to add one or more packages in order to extend LaTeX’s functionality. Packages are collections of commands and environments that add new features to LaTeX, for example:

- Changing how some parts of LaTeX work.

- Adding new commands.

- Changing the appearance/design of the document.

We can add a package to our document by using the

\usepackage command in the preamble of our document. For

example, to add the geometry package to our document, we

would add the following line to the preamble:

In addition to the name of the package in the curly braces, we can also add options to the package by adding them in square brackets before the package name. For example, to set the width of the text block in our document to 6cm, we would update this line to look like this:

Give this a try in our main.tex document to see what

happens. When you render the document, you should see something like

this:

However this isn’t what we really want, so we’ll remove this line from our document.

Changing the Design

It’s useful to be able to adjust some aspects of the design

independent of the document class, for example, the page margins. We

used the geometry package in our previous example to set

the width of the text block, but now let’s use it to specifically set

the margins of our document:

So far we’ve been showing the entire document in the examples. Going

forward, we’ll only show the relevant sections of the document that

we’re discussing, so keep in mind when we are talking about “adding this

to the preamble” we mean adding it to the section of the document

before the \begin{document} command.

Let’s add this to the preamble of our document:

You should see that adding this package and setting the “margin”

option to 1in has shrunk the margins of the document (try

commenting out the \usepackage line with a %

and recompiling to see the difference).

Defining Custom Commands

Using other people’s packages is great, but what if there is some

kind of functionality we want to add to our document that isn’t covered

by a package? Or some specific formatting we want to use repeatedly? We

can define our own commands in LaTeX using the \newcommand

command.

The \newcommand syntax looks like this:

We could be even more flexible by using an optional argument

in our \newcommand. Then the general structure of the

command looks like this

LATEX

\newcommand{\commandname}[number of arguments][default value for the first argument]{definition}You can learn more about optional arguments in the last challenge of this episode.

As an example, let’s define a command that will highlight specific

works in a document, so that they appear italicised and underlined. We

could do this by writing \textbf{\underline{word}}

around each word we want to highlight:

LATEX

This is my first \textbf{\underline{LaTeX}} document.

\section{Sections}

I can add content to my first \textbf{\underline{section}}!We can add this to each of our important terms in our document - maybe it looks something like this:

In a long document this would quickly become tedious. Instead, let’s

define a new command called \kw in the preamble of our

document that will do this for us:

LATEX

% The \newcommand defines a new custom command

% Highlight Keywords using the \kw{} command

\newcommand{\kw}[1]{\textbf{\underline{#1}}}Now we can use the \kw command to highlight words in our

document:

LATEX

This is my first \kw{LaTeX} document.

\section{Sections}

I can add content to my first \kw{section}!Let’s take a minute to go through and add the \kw

command to all the keywords in our document.

- LaTeX

- section

- subsection

- lists

- ordered

- unordered

Related to the \newcommand command, we can also use the

\renewcommand command to change the definition of an

existing command. This is useful, for example, if we want to change the

effect of a command partway through a document, or if we want to change

the definition of a command that is already defined in a package. It has

an identical syntax to the \newcommand command:

Code Reuse

This also means that we can easily change the formatting of all the

words we’ve highlighted by updating the definition of the

\kw command. Let’s say we wanted to change the formatting

to bold and change the color to blue:

Let’s replace our \kw command with this new definition:

\newcommand{\kw}[1]{\textcolor{blue}{\textbf{#1}}}

When we recompile the document we should see that the formatting of our keywords has changed all at once:

Defining Multiple Commands

We can define as many commands as we like in the preamble of our document. Let’s add another one that we can use to highlight commands in the document:

We’ll use this command in later sections.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Importing a new package

A useful package to preview what your document will look like before

your write a lot of text is the lipsum package. This

package provides sample text blocks from a common placeholder text.

How would you add the lipsum package to the preamble of your document?

Add the line \usepackage{lipsum} to the preamble of your

document.

You can then use the \lipsum command in the body of your

document to add some dummy text.

Challenge 2: What does this mean?

The definition of a new command in LaTeX is done with the

\newcommand command. The syntax for this command is:

So if we modify the \kw command we defined above to look

like this:

What would the new \kw command do? and how would we use

it?

Challenge 3: Can you write your own command with two arguments?

Suppose you want to define a new command that takes as input two words as arguments. This first word shall be written bold while the second word shall be written italic. Moreover, the first and the second word are separated by a comma followed by a whitespace.

Use \newcommand to define this command that takes two

arguments as inputs and name it \bo_it. Write the following

sentence into your LaTeX document using your new command

\bo_it:

This newly defined command highlights these two words: Apple, Banana.

The new \boit command would take two arguments: the

first argument would be used with \tetxbf{#1} to make the

first word appear bold, and the second argument would

be used with \tetxit{#2} to make the first word appear

italic. Between \tetxbf{#1} and

\tetxit{#2}, we would write , to separate both

words. We would use the new command like this:

Challenge 4: Optional arguments

New commands can be made even more flexible by defining commands that take an optional argument. Then the general LaTeX code for this looks like this:

LATEX

\newcommand{\commandname}[number of arguments][default value for the first argument]{definition}The optional argument can be accessed and changed by writing square

brackets [] directly after the \commandname in

the body of your document.

Consider the following, modified example of our \kw from

before where we now use an optional argument.

In your LaTeX file, use the new \kw command to write

down the words “Banana” in yellow, “Apple” in red, and “Blueberry” in

blue. Each word should be written in a separate line.

We can exploit the optional argument in \kw to write

down the given words very efficiently. For the first word, we change the

optional argument to “yellow”. For the second word, we stick with the

default value of “red”. For the third word, we change the optional

argument to “blue”.

- We can extend LaTeX’s functionality by adding packages to our document.

- We can define custom commands in LaTeX using the

\newcommandcommand.

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like.

Content from Using Graphics

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I include images in a LaTeX document?

Objectives

- Demonstrate how to include images in a LaTeX document.

- Show how to position images manually / automatically in a LaTeX document.

The Graphicx Package

In order to use graphics in our document, we’ll need to use the

graphicx package, which adds the

\includegraphics command to LaTeX. We’ll add this to the

preamble of our document:

We can now include several types of images in our document, including:

- JPEG

- PNG

- EPS

For the purposes of this lesson, we’ll use the following image:

Download this image to your computer either be right-clicking on the image and selecting “Save Image As…” or by clicking on the image and saving it from the browser.

You can use any image you like for this lesson. Just make sure to

replace example-image.PNG with the name of your image in

the following examples.

Place the image in the same directory as your LaTeX document so that LaTeX can find it when we compile the document.

Including an Image in a LaTeX Document

Now that we have our image, we can include it in our document using

the \includegraphics command:

LATEX

\section{Graphics}

We can include \kw{images} in our document using the \cmd{graphicx} package, which lets us use the

\cmd{includegraphics} command.

\includegraphics{example-image.PNG}Your document should now look like this:

If you just want to see how an image might look in your document

without having to find one, you can use the filepath

example-image in the \includegraphics command.

This will display a placeholder image in your document that you can

replace later.

Adjusting the appearance of the image

But wait! The image is too big, and it doesn’t fit on the page, so LaTeX has moved it to the next page. Since the image is a little too large to fit on the same page as the text, LaTeX has moved it automatically to the next page. Let’s address that by making the image smaller.

We can adjust the appearance of the image by passing options to the

\includegraphics command, just like we did earlier with the

geometry package. For example, we can specify the height of

the image:

LATEX

\subsection{Small Image}

We can pass parameters to the \cmd{includegraphics} command to adjust the appearance of the image.

\includegraphics[height=2cm]{example-image.PNG}

Other possible options include:

\begin{itemize}

\item width: the width of the image

\item scale: the scaling factor of the image

\item angle: the angle of rotation of the image

\item clip: whether to clip the image to its bounding box

\item trim: trim the image by a specified amount

\item draft: display a box instead of the image

\end{itemize}Some other possible options from the graphicx package

include:

-

width: the width of the image -

scale: the scaling factor of the image -

angle: the angle of rotation of the image -

clip: whether to clip the image to its bounding box -

trim: trim the image by a specified amount -

draft: display a box instead of the image

Positioning the image

We can place the image inside of an environment to help position it

in the document. Let’s try placing the \includegraphics

command inside of a \begin{center} and

\end{center} environment:

LATEX

\subsection{Centered Image}

By placing the \cmd{includegraphics} command inside a center environment, we can center the

image on the page.

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[height=2cm]{example-image.PNG}

\end{center}You should see that the image is now centered on the page:

“Floating” Images

It’s often the case that images need to “float” around the document as new text is added or removed. this is called a “floating” image. Images are normally included as floats so that we don’t end up with large gaps in the document.

To make an image float, we can use the figure

environment:

LATEX

\subsection{Floating Image}

\kw{Floating images} can move around the page as text is added or removed. We can use the

\cmd{figure}environment to create a floating image.

\begin{figure}

\centering

\includegraphics[height=2cm]{example-image.PNG}

\end{figure}When we render the document, we can see that, even though we placed the image at the end of the document, it appears at the top of the page:

You might have noticed that instead of using the

\begin{center} and \end{center} environment,

we used the \centering command inside of the

figure environment. This is because the figure

environment is a floating environment, and the \centering

command is the recommended way to center content inside of a floating

environment.

Controlling the Position of a Floating Image

We can pass parameters to the figure environment to

control the position of the floating image:

-

h: Place the float “here” (where it appears in the code) -

t: Place the float at the “top” of the page -

b: Place the float at the “bottom” of the page -

p: Place the float on a “page” by itself

It is also possible to combine these options. For example, to place

the float here if possible, but otherwise at the top of the page, we can

use the ht option. Let’s update our figure

environment to use the ht option:

LATEX

\begin{figure}[ht]

\centering

\includegraphics[height=2cm]{example-image.PNG}

\end{figure}

Control the position of a floating image by passing parameters to the \cmd{figure} environment:

\begin{itemize}

\item h: Place the float "here" (where it appears in the code)

\item t: Place the float at the "top" of the page

\item b: Place the float at the "bottom" of the page

\item p: Place the float on a "page" by itself

\end{itemize}You can use the package wrapfig together with

graphicx in your preamble. This makes the

wrapfigure environment available and we can place an

\includegraphics command inside it to create a figure

around which text will be wrapped. Here is how we can specify a

wrapfigure environment:

We will describe the wrapfigure environment in more

detail in one of the challenges below.

Adding a Caption

We can add a caption to our image by using the \caption

command inside of the figure environment:

LATEX

\subsection{Caption}

We can add a \kw{caption} to our floating image by using the \cmd{caption} command inside of the

\cmd{figure} environment.

\begin{figure}

\centering

\includegraphics[height=2cm]{example-image.PNG}

\caption{This is a caption for our image.}

\end{figure}When we render the document, we can see that the caption appears below the image:

Note that the caption is automatically numbered “Figure 1”. Very handy! We’ll see how we can automatically reference figures and tables in a later episode.

Another package that we can use to work with images in LaTeX is the

hvfloat package. This package is an alterantive way of

controlling the position of floating elemnents in LaTeX, like images and

tables. It provides a more flexible way of positioning floats allowing

us to, for example, place a float at the bottom of the page, even if

there is not enough space for it to fit.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Can you do it?

Consider again our running example of example-image.PNG.

Include this image into your LaTeX document by using the

figure environment. Make sure that your image is centered

and rotate the image by 45 degree. Add the following caption to your

image: “This caption has a bold word included.” How

would your LaTeX look like?

We use the \centering command in the figure

environment and specify angle=45 to rotate the image.

Challenge 2: What is wrong here?

Have a look at the following LaTeX code:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

\centering

\begin{figure}

\includegraphics[height=3cm, draft]{example-image.PNG}

\caption{This caption has a \textbf{bold} word included.}

\end{figure}

\end{document}Can you spot all the errors in this LaTeX code? Change the code such that the image is displayed with a height of 3cm, width of 4cm and centered.

First, the command \usepackage{graphicx} is missing in

the preamble. Second, the \centering command has to be

placed into the figure environment. Third, the

draft argument has to be removed from and

width=4cm added to the \includegraphics

command.

The corrected LaTeX code looks like this:

Challenge 3: Making a command for images

In the previous section, we created a command to highlight keywords

in our document. Let’s create a new command to make it easier to include

images in our document. We’ll create a command called

\centeredimage that takes two arguments: the image filename

and the caption. The resulting image should be centered on the page and

have a caption below it. Use the example-image.png from earlier in this

episode.

Your file should look like this:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{graphicx}

% Define our new command

%%% YOUR COMMAND HERE %%%

\begin{document}

\centeredimage{example-image.png}{"My Image"}

\centeredimage{example-image.png}{"My Other Image"}

\end{document}And your output should look like this.

Reminder: The syntax for creating a new command is:

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{graphicx}

% Define our new command

\newcommand{\centeredimage}[2]{

\begin{figure}

\centering

\includegraphics{#1}

\caption{#2}

\end{figure}

}

\begin{document}

\centeredimage{example-image.png}{"My Image"}

\centeredimage{example-image.png}{"My Other Image"}

\end{document}Challenge 4: The wrapfig

package.

Have a look at the following LaTeX code that uses the

wrapfigure environment. Can you already guess how the

images will be displayed in your document?

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{wrapfig}

\usepackage{graphicx}

\begin{document}

\begin{wrapfigure}{r}{0.1\textwidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.1\textwidth, height=0.1\textwidth]{example-image.PNG}

\end{wrapfigure}

The package wrapfigure lets you position images around your text.

That comes in handy if you want to integrate images seamlessly into your written sentences.

Therefore, I add a few more sentences here to showcase this integration to you.

\begin{wrapfigure}{l}{0.1\textwidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.1\textwidth, height=0.1\textwidth]{example-image.PNG}

\end{wrapfigure}

Be careful, you need both packages, wrapfig and graphicx, in your preamble to display your images

and wrap them accordingly. There are several ways to display images, depending on the arguments you

specify. For instance, you can scale the image width according to the width of the text.

\end{document}The first image will be placed at the right of the following

paragraph of text as {r} is specified as an argument within

the first wrapfigure environment. The second image will be

placed at the left of its following paragraph of text as

{l} is specified as an argument within the second

wrapfigure environment. Moreover, both images are scaled by

being 0.1 of the width of the text in your document.

- The

graphicxpackage allows us to include images in our LaTeX document. - We can adjust the appearance of images using options in the

\includegraphicscommand. - We can position images manually or automatically using environments

like

centerandfigure. - Floating images can move around the page as text is added or removed.

- We can control the position of floating images using parameters in

the

figureenvironment. - We can add captions to floating images using the

\captioncommand.

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like.

Content from Tables

Last updated on 2025-07-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I add tables to a LaTeX document?

- How can I format a table in a LaTeX document?

Objectives

- Create a table in a LaTeX document.

- Customize the appearance of a table in a LaTeX document.

- Add horizontal lines to a table in a LaTeX document.

Defining Tables

Tables in LaTeX are set using the tabular environment.

For our purposes here, we are going to use the array

package to create a table, which provides additional functionality for

creating tables. We’ll add this to the preamble of our document:

As we start to add more and more packages to our preamble, it can get a bit unwieldy. For now, let’s just keep them alphabetized to make it keep things organized. Our imports should now look like this:

In order to create a table, we need to tell latex how many columns we will need and how they should be aligned.

Available column types are:

| Column Type | Description |

|---|---|

l |

left-aligned |

c |

centered |

r |

right-aligned |

p{width} |

a column with fixed width; the text will be automatically line wrapped and fully justified |

m{width} |

like p, but vertically centered compared to the rest of the row |

b{width} |

like p, but bottom aligned |

w{align}{width} |

prints the contents with a fixed width, silently overprinting if things get larger. (You can choose the horizontal alignment using l, c, or r.) |

W{align}{width} |

like w, but this will issue an overfull box warning if things get too wide. |

The columns l, c and r will have the natural width of the widest

entry in the column. Each column must be declared, so if you want a

table with three centered columns, you would use ccc as the

column declaration.

Creating a Table

Now that we have the array package loaded and we know how to define

columns, we can create a table using the tabular

environment.

Note that the & and \\ characters are

aligned in our example. This isn’t strictly necessary in LaTeX, but it

makes the code much easier to read.

LATEX

\section{Tables}

\kw{Tables} are defined using the \cmd{tabular} environment.

\begin{tabular}{lll}

Fruit & Quantity & Price \\

Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\end{tabular}This will create a table with three columns, all left-aligned. The

values of each row are separated by & and the rows are

separated by \\. We do not yet have any horizontal lines in

the table, so it will look like this:

If your table has many columns, it may get cumbersome to write out

the column definitions every time. In this case you can make things

easier by using *{num}{string} to repeat the string

num times. For example, in our table above, we can instead

write:

Adding Horizontal Lines

We’re going to introduce another package here: booktabs.

This package provides a few commands that make it easier to create

professional looking tables. To use it, add the following to your

preamble:

booktabs provides three commands for creating horizontal

lines in your table:

-

\toprule: creates a line at the top of the table -

\midrule: creates a line in the middle of the table -

\bottomrule: creates a line at the bottom of the table

Horizontal lines make tables easier to read and understand, and they can be used to separate the header from the body of the table, and the body from the footer. We can insert these commands into our table to add horizontal lines:

LATEX

\subsection{Tables with Horizontal Lines}

We can use the \cmd{\textbackslash toprule}, \cmd{\textbackslash midrule}, and

\cmd{\textbackslash bottomrule} commands from the \cmd{booktabs} package to create horizontal

lines in our table.

\begin{tabular}{*{3}{l}}

\toprule

Fruit & Quantity & Price \\

\midrule

Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}Your table should look something like this:

A general recommendation is to use lines sparsely in your tables, and vertical lines should be avoided.

Partial Horizontal Lines

Another useful feature of booktabs is the ability to

create partial horizontal lines with the \cmidrule command.

This command accepts the arguments {number-number}, where the first

number is the column to start the line and the second number is the

column to end the line.

LATEX

\subsection{Partial Horizontal Lines}

The \cmd{\textbackslash cmidrule} command can be used to create partial horizontal lines in a

table. The command accepts the arguments {number-number}, where the first number is the column to

start the line and last number is the column to end the line.

\begin{tabular}{*{3}{l}}

\toprule

Fruit & Quantity & Price \\

\midrule

Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\cmidrule{3-3}

Total & 15 & 28.20 \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}This table should come out looking something like this:

Merging Cells

We can merge cells horizontally using the \multicolumn

command. This command takes three arguments:

- The number of cells which should be merged

- The alignment of the merged cell (l, c, or r)

- The contents of the merged cell

LATEX

\subsection{Merging Cells}

Merge cells horizontally using the \cmd{\textbackslash multicolumn} command. This command takes

three arguments:

\begin{itemize}

\item The number of cells which should be merged

\item The alignment of the merged cell (l, c, or r)

\item The contents of the merged cell

\end{itemize}

\begin{tabular}{*{3}{l}}

\toprule

\multicolumn{3}{c}{Overall Inventory} \\

Fruit & Quantity & Price \\

\midrule

Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{2}{c}{Summary} \\

Total & 15 & 28.20 \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}Vertical merging is supported in LaTeX by using the

multirow package which has the \multirow

command equipped with it. It is similarly structured as

\multicolumn by using three arguments:

- The number of rows which should be merged

- The width of the column (i.e. 4em)

- The contents of the merged rows.

You can find an example in the challenges below.

This will create a table that looks like this:

Challenges

Challenge 1: Can you do it?

Try to replicate the following table in LaTeX:

| Make | Model | Sold |

|---|---|---|

| Volkswagen | Golf | 7,687 |

| Skoda | Octavia | 4,078 |

| Seat | Leon | 3,922 |

| Volkswagen | Passat | 3,776 |

| Mercedes | GLK,GLC | 3,143 |

| Total | 22,606 |

Your LaTaX version should look something like this.

Note that the last row is a bit different from the others. The first two columns re merged, the text “Total” is right-aligned and bold, and the value in the last column is italicized.

(Data for this challenge is from Statista)

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{array}

\usepackage{booktabs}

\begin{document}

\begin{tabular}{lll}

\toprule

Make & Model & Sold \\

\midrule

Volkswagen & Golf & 7,687 \\

Skoda & Octavia & 4,078 \\

Seat & Leon & 3,922 \\

Volkswagen & Passat & 3,776 \\

Mercedes & GLK,GLC & 3,143 \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{2}{r}{\textbf{Total}} & \textit{22,606} \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

\end{document}Challenge 2: Merging rows.

Consider the following LaTeX code that creates a table using the

command \multirow. Can you guess how this table will look

like? How many columns will it have? How many rows? Are any rows or

columns combined?

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{booktabs}

\usepackage{multirow}

\begin{document}

\begin{tabular}{*{4}{l}}

\toprule

& Food & Quantity & Price \\

\midrule

\multirow{3}{4em}{Fruit} & Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

& Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

& Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\midrule

\multirow{2}{4em}{Cheese} & Brie & 2 & 3.30 \\

& Asiago & 3 & 2.90 \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

\end{document}The table will have 4 columns where the first column does not have a column name. The table will have 6 rows. The first row is the column name row. Rows 2 to 4 are merged for “Fruit”. Rows 5 and 6 are merged for “Cheese”.

Hint: We want to make sure the caption stays with the table, so we should put the table inside an environment. For images we use the “figure” environment, but for tables we can use the “table” environment.

Challenge 3: Adding merged rows to your table.

Consider again the LaTeX code for the table in challenge 2. Add four more rows to this table that contain information about the following four sorts of bread:

- Brioche, 3, 3.00

- Bagel, 2, 3.50

- Matzah, 4, 3.60

- Naan, 2, 3.40

Use \multirow to subsume those bread types under the

category “Bread”.

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{booktabs}

\usepackage{multirow}

\begin{document}

\begin{tabular}{*{4}{l}}

\toprule

& Food & Quantity & Price \\

\midrule

\multirow{3}{4em}{Fruit} & Apple & 5 & 1.50 \\

& Banana & 6 & 2.00 \\

& Orange & 4 & 1.20 \\

\midrule

\multirow{2}{4em}{Cheese} & Brie & 2 & 3.30 \\

& Asiago & 3 & 2.90 \\

\midrule

\multirow{4}{4em}{Bread} & Brioche & 3 & 3.00 \\

& Bagel & 2 & 3.50 \\

& Matzah & 4 & 3.60 \\

& Naan & 2 & 3.40 \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

\end{document}Challenge 4: Making the Table Colorful

We used the xcolor package to add color to our text in

an earlier episode. Can you use the xcolor package to make

the header and summary rows of the table in Challenge 1 a different

color? What about changing the color of the text in the summary row? Can

we make the rows of the table alternate colors?

A few things that will help you:

- We need to import the

xcolorpackage in the preamble of our document. - The

xcolorpackage doesn’t automatically support coloring tables, so we need to add thetableoption to the package import. \rowcolor{(<color>}\rowcolors{<starting row number>}{<color1>}{<color2>}- You can make lighter versions of colors by adding

!<percentage>to the color name. For example,red!10is a light red color, whilered!90is a darker red color.

There’s no right answer to this challenge, so feel free to experiment with different colors! Here’s an example of what you can do.

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{array}

\usepackage{booktabs}

\usepackage[table]{xcolor} % Import xcolor with the table option

\begin{document}

\begin{table}[ht]

\centering

\rowcolors{2}{red!10}{gray!10} % Alternate row colors between red and gray

\begin{tabular}{lll}

\toprule

\rowcolor{green!20} % Set the header row color to green

Make & Model & Sold \\

\midrule

Volkswagen & Golf & 7,687 \\

Skoda & Octavia & 4,078 \\

Seat & Leon & 3,922 \\

Volkswagen & Passat & 3,776 \\

Mercedes & GLK,GLC & 3,143 \\

\midrule

\rowcolor{blue!20} % Set the summary row color to blue

\multicolumn{2}{r}{

% Set the text color to blue and bold for the summary row

\textbf{\textcolor{blue!75}{Total}}} & \textit{\textcolor{blue!75}{22,606}} \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

\caption{Car Sales by Make/Model (January 2025)} % Add a caption to the table

\end{table}

\end{document}- Tables in LaTeX are created using the

tabularenvironment. - The

arraypackage provides additional functionality for creating tables. - The

booktabspackage provides commands for creating horizontal lines in tables. - The

\multicolumncommand can be used to merge cells in a table. - The

\multirowcommand in themultirowpackage can be used to merge rows in a table.

After this episode, here is what our LaTeX document looks like.

Content from Adding Cross References

Last updated on 2025-08-18 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I ensure that numbers in my document are automatically updated?

- How can I refer to numbered elements in my document?

Objectives

- Insert a cross-reference in a LaTeX document.

- Refer to a cross-referenced element in a LaTeX document.

Cross References

When writing a document of any length, you’ll often want to refer to numbered elements such as figures, tables, equations, or sections. LaTeX provides a way to automatically number these elements and refer to them in your text.

Label and Ref

To have LaTex remember a specific spot in your document, you have to

use the \label{} command to mark it, and the

\ref{} command to refer to it. For example:

LATEX

\section{Cross References}

\label{sec:cross-references}

\subsection{Material for the Introduction}

In this section, we introduce two new concepts:

\begin{tabular}{cp{9cm}}

\toprule

Command & Description \\

\midrule

\kw{label} & Marks a spot in the document \\

\kw{ref} & Refers to a marked spot in the document \\

\bottomrule

\label{tab:cross-reference-commands}

\end{tabular}

We can \kw{refer} to the section with the \cmd{ref} command, like this: \ref{sec:cross-references}.

We can likewise refer to the table like this: \ref{tab:cross-reference-commands}.The sec and tab prefixes in the

\label{} command are not required, but they help to

identify the type of element being labeled. This is especially useful

when you have many labels in your document.

When you hit compile, you may notice that the \ref{}

command does not return the correct references and instead shows

question marks (??). This is because LaTeX needs to compile the document

twice. Once to gather all the labels and references, and a second time

to resolve them. If you see question marks, just compile the document

again, and it should work correctly.

The label command always refers to the previous numbered entry: a

section, a table, a figure, etc. This means that the

\label{} command should always come after the

numbered element you want to refer to.

Note that the ref command does not insert the section or

table name, but rather the number associated with it. We would still

write “Refer to Table \(\ref{tab:cross-reference-commands}\)”, but

the benefit is that if the table number changes because we’ve added or

removed sections before it, the reference will update automatically.

There are packages that can provide more advanced cross-referencing

capabilities, such as the cleveref package, which can

automatically detect the type of element being referenced and insert the

appropriate name. For more details about this, refer to the references

section.

cleveref allows the format of cross-references to be

formatted automatically, so that the “type” of the referenced element

(e.g., figure, table, section) is included in the reference text. The

\cref command is used to create these references.

If you want the references to be clickable in the PDF, you can use

the hyperref package:

This package automatically makes all references clickable, allowing you to jump to the referenced element in the PDF document. However be aware that this can sometimes cause issues with other packages, so it’s best to load it last in your preamble.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Add a figure, then reference it.

In your LaTeX document, include the image

example-image.PNG and cross-reference it in the text. Make

sure the figure has a caption and is labeled and centered properly. Use

the \includegraphics command to add the image and wrap it

in a figure environment. Then, refer to it in the text

using the \ref command.

You may find the following LaTeX template helpful.

As shown in \(\ref{tab:findings}\) post-treatment values are higher…

LATEX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{graphicx}

\begin{document}

\section{Cross-referencing Figures}

Here is an example of a figure in the document. We will refer to it later in the text.

\begin{figure}[ht]

\centering

\includegraphics[height=4cm]{example-image.PNG}

\caption{This is an example figure.}

\label{fig:example-image}

\end{figure}

In the text, we can refer to the figure using its label: Figure \ref{fig:example-image}.

\end{document}Challenge 2: Where does the reference go?

We mentioned that the \label{} command should always

come after the numbered element you want to refer to. What do you think

would happen if we put the \label{} command before the

numbered element? For example:

LATEX