Inheritance and Composition

Last updated on 2025-09-28 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 12 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does Composition differ from Inheritance?

- When should I use Composition over Inheritance?

Objectives

- Explain the difference between Inheritance and Composition

- Use Composition to build classes that contain instances of other classes

Composition

In the previous episode, we saw how to use Inheritance to create a specialized version of an existing class. But there’s another strategy we can use to build classes: Composition. Composition is a design principle where a class is composed of one or more objects from other classes, rather than inheriting from them. This allows us to create complex functionality by combining several smaller, simpler classes.

Back to the Car Example

Let’s revisit our Car example from the Class Objects

episode. As a reminder, our class looked like this:

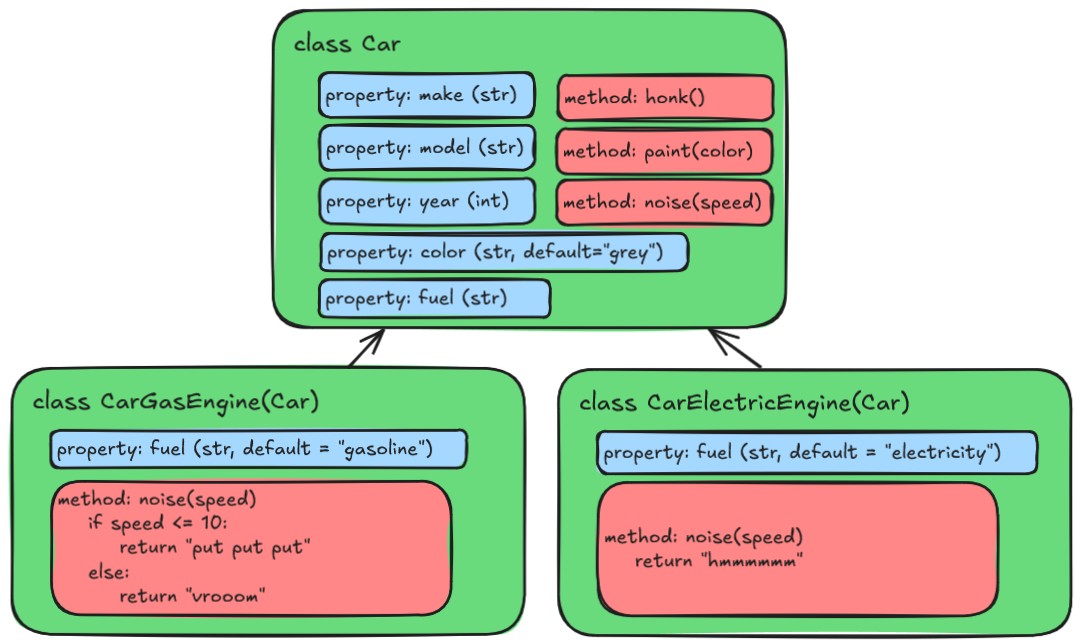

But what if we wanted to add more functionality to our

Car class? We talked about in the previous episode how we

could use Inheritance to create specialized versions of the

Car class, like this:

The code might look something like this:

PYTHON

class Car:

def __init__(self, make: str, model: str, year: int, color: str = "grey", fuel: str = None):

self.make = make

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

def honk(self) -> str:

return "beep"

def paint(self, new_color: str) -> None:

self.color = new_color

def noise(self) -> str:

raise NotImplementedError("Subclasses must implement this method")

class CarGasEngine(Car)

def __init__(self, make: str, model: str, year: int, color: str = "grey"):

super().__init__(make, model, year, color, fuel="gasoline")

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

if speed <= 10:

return "put put put"

elif speed > 10:

return "vrooom"

class CarElectricEngine(Car)

def __init__(self, make: str, model: str, year: int, color: str = "grey"):

super().__init__(make, model, year, color, fuel="electric")

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

return "hmmmmmm"But what happens if we start adding more kinds of engines? Or if our

engines start getting more complex, with different properties and

methods? Even worse, what if we want to add a new type of car component,

like Wheels? Do we now need to start creating subclasses

for every possible combination of car, engine, and wheels? We would end

up with a lot of subclasses, some of which might have extremely similar

(if not identical) functionality.

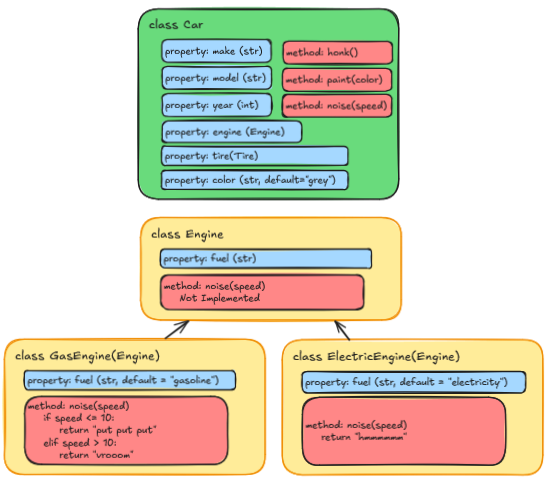

Instead, we can use a Compositional approach by making a new kind of

class called Engine, and then including an instance of that

class as a property of the Car class. This way, we can

create different kinds of engines as separate classes, and then use them

in our Car class without having to create a new subclass

for each one. Here’s how that would look:

PYTHON

class Car:

def __init__(self, make: str, model: str, year: int, color: str = "grey", engine: Engine = None):

self.make = make

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.engine = engine

def honk(self) -> str:

return "beep"

def paint(self, new_color: str) -> None:

self.color = new_color

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

if self.engine:

return self.engine.noise(speed)

raise ValueError("Car must have an engine")

class Engine:

def __init__(self, fuel: str):

self.fuel = fuel

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

raise NotImplementedError("Subclasses must implement this method")

class GasEngine(Engine):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__(fuel="gasoline")

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

if speed <= 10:

return "put put put"

elif speed > 10:

return "vrooom"

class ElectricEngine(Engine):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__(fuel="electric")

def noise(self, speed: int) -> str:

return "hmmmmmm"At first glance this might look even more complicated, but it has several advantages:

-

Separation of Concerns: The

Engineclass is responsible for engine-specific behavior, while theCarclass focuses on car-specific behavior. This makes the code easier to understand and maintain. -

Reusability: The

Engineclass can be reused in other contexts, such as in aTruckorMotorcycleclass, without duplicating code. -

Flexibility: We can easily add new types of engines

by creating new subclasses of

Engine, without having to modify theCarclass or create new subclasses ofCar.

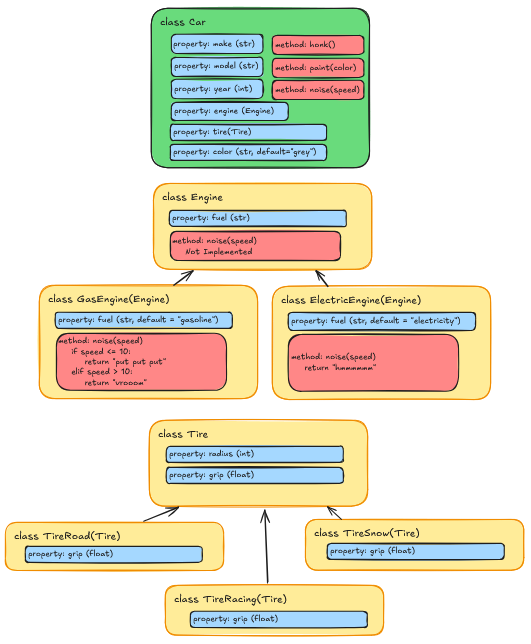

Think about if we added a Tire class as well. We could

have different types of tires (e.g., Road Tires, Racing Tires, Snow

Tires, etc.) and then include an instance of the Tire class

in the Car class. This would allow us to mix and match

different types of engines and tires without having to create a new

subclass for every possible combination.

Refactoring our Document Example

Let’s take this concept and apply it to our Document

example from previous episodes. We can create a new class called

Reader that is responsible for reading files and providing

the content to the Document class. We can have a different

reader type for each file format we want to support.

To start with, let’s create a directory for our readers called

readers, and then create a base class called

BaseReader in a file called

readers/base_reader.py:

PYTHON

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class BaseReader(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def get_content(self, filepath: str) -> str:

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_metadata(self, filepath: str) -> dict:

passThen we’ll create a TextReader class in a file called

readers/text_reader.py. We’ll move over the logic for

reading and extracting content from a Project Gutenberg text file

here:

PYTHON

import re

from .base_reader import BaseReader

class TextReader(BaseReader):

TITLE_PATTERN = r"^Title:\s*(.*?)\s*$"

AUTHOR_PATTERN = r"^Author:\s*(.*?)\s*$"

ID_PATTERN = r"^Release date:\s*.*?\[eBook #(\d+)\]"

CONTENT_PATTERN = r"\*\*\* START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK .*? \*\*\*(.*?)\*\*\* END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK .*? \*\*\*"

def read(self, filepath: str) -> str:

with open(filepath, encoding="utf-8") as file_obj:

return file_obj.read()

def _extract_metadata_element(self, pattern: str, text: str) -> str | None:

match = re.search(pattern, text, re.MULTILINE)

if match:

return match.group(1).strip()

return None

def get_content(self, filepath: str) -> str:

raw_text = self.read(filepath)

match = re.search(self.CONTENT_PATTERN, raw_text, re.DOTALL)

if match:

return match.group(1).strip()

raise ValueError(f"File {filepath} is not a valid Project Gutenberg Text file.")

def get_metadata(self, filepath: str) -> dict:

raw_text = self.read(filepath)

title = self._extract_metadata_element(self.TITLE_PATTERN, raw_text)

author = self._extract_metadata_element(self.AUTHOR_PATTERN, raw_text)

extracted_id = self._extract_metadata_element(self.ID_PATTERN, raw_text)

return {

"title": title,

"author": author,

"id": int(extracted_id) if extracted_id else None,

}Next, we’ll do the same for the HTML code. Create a file called

readers/html_reader.py:

PYTHON

import re

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from .base_reader import BaseReader

class HTMLReader(BaseReader):

URL_PATTERN = "^https://www.gutenberg.org/files/([0-9]+)/.*"

def read(self, filepath) -> BeautifulSoup:

with open(filepath, encoding="utf-8") as file_obj:

parsed_file = BeautifulSoup(file_obj, features="html.parser")

if not parsed_file:

raise ValueError("The file could not be parsed as HTML.")

return parsed_file

def get_content(self, filepath) -> str:

parsed_file = self.read(filepath)

# Find the first h1 tag (The book title)

title_h1 = parsed_file.find("h1")

# Collect all the content after the first h1

content = []

for element in title_h1.find_next_siblings():

text = element.get_text(strip=True)

# Stop early if we hit this text, which indicate the end of the book

if "END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK" in text:

break

if text:

content.append(text)

return "\n\n".join(content)

def get_metadata(self, filename) -> str:

parsed_file = self.read(filename)

title = parsed_file.find("meta", {"name": "dc.title"})["content"]

author = parsed_file.find("meta", {"name": "dc.creator"})["content"]

url = parsed_file.find("meta", {"name": "dcterms.source"})["content"]

extracted_id = re.search(self.URL_PATTERN, url, re.DOTALL)

id = int(extracted_id.group(1)) if extracted_id.group(1) else None

return {"title": title, "author": author, "id": id}Finally, we can update our Document class to use these

readers. We’ll add a new parameter to the Document

constructor called reader, which will be an instance of a

BaseReader subclass. Here’s how the updated

Document class might look:

PYTHON

from textanalysis_tool.readers.base_reader import BaseReader

class Document:

@property

def gutenberg_url(self) -> str | None:

if self.id:

return f"https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/{self.id}/pg{self.id}.txt"

return None

@property

def line_count(self) -> int:

return len(self.content.splitlines())

def __init__(self, filepath: str, reader: BaseReader):

self.filepath = filepath

self.content = reader.get_content(filepath)

metadata = reader.get_metadata(filepath)

self.title = metadata.get("title")

self.author = metadata.get("author")

self.id = metadata.get("id")

def get_word_occurrence(self, word: str) -> int:

return self.content.lower().count(word.lower())Key Points

Ok, that’s a lot of changes. So what was that all about?

- Modularity: Our code is now made up of smaller, more focused classes. The code responsible for reading files in and parsing the contents is separate from the code that represents a document and provides analysis.

-

Extensibility: We can easily add support for new

file formats by creating new reader classes that inherit from

BaseReader, without having to modify theDocumentclass. - Maintainability: Each class has a single responsibility, making it easier to understand and maintain.

- Reusability: The reader classes can be reused in other contexts, such as in a different application that needs to read and parse files.

Also note that in the Document class, in the

__init__ method, the typehint for the reader

parameter is BaseReader. This means that any subclass of

BaseReader can be passed in, allowing for flexibility in

the type of reader used.

By using Inheritance and an abstract base class for the reader, we

are essentially creating a promise that any subclass of

BaseReader will implement the methods defined in the base

class. This is how we can safely call reader.get_content()

and reader.get_metadata() in the Document

class - we no longer care what specific type of reader it is, as long as

it adheres to the abstract base class interface.

Testing the New Objects

We can now delete our two inherited classes DocumentText

and DocumentHTML, and update our tests to use the new

TextReader and HTMLReader classes. This,

however means that we need to rewrite our tests to use the new

Document constructor, which requires a

BaseReader subclass instance.

Because of our new Compositional design, we can now test the

Document without a specific reader by using a mock reader.

This allows us to isolate the Document class and test its

functionality without relying on the actual file reading and parsing

logic:

PYTHON

import pytest

from textanalysis_tool.document import Document

from textanalysis_tool.readers.base_reader import BaseReader

class MockReader(BaseReader):

def get_content(self, filepath: str) -> str:

return "This is a test document. It contains words.\nIt is only a test document."

def get_metadata(self, filepath: str) -> dict:

return {

"title": "Test Document",

"author": "Test Author",

"id": 1234,

}

def test_create_document():

doc = Document(filepath="dummy_path.txt", reader=MockReader())

assert doc.title == "Test Document"

assert doc.author == "Test Author"

assert isinstance(doc.id, int) and doc.id == 1234

def test_line_count():

doc = Document(filepath="dummy_path.txt", reader=MockReader())

assert doc.line_count == 2

def test_get_word_occurrence():

doc = Document(filepath="dummy_path.txt", reader=MockReader())

assert doc.get_word_occurrence("test") == 2This time we are using a MockReader class that

implements the BaseReader interface. We could also use a

fixture here, but this is simpler for demonstration purposes.

Challenge 1: Writing Tests for the Readers

Now that we have our TextReader and

HTMLReader classes, we need to write tests for them. Create

a new directory called tests/readers, and then create two

new test files: test_text_reader.py and

test_html_reader.py. Write tests for the

get_content and get_metadata methods of each

reader based on our previous tests for the

PlainTextDocument and HTMLDocument

classes.

tests/readers/test_text_reader.py

PYTHON

import pytest

from unittest.mock import mock_open

from textanalysis_tool.readers.text_reader import TextReader

TEST_DATA = """

Title: Test Document

Author: Test Author

Release date: January 1, 2001 [eBook #1234]

Most recently updated: February 2, 2002

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TEST ***

This is a test document. It contains words.

It is only a test document.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TEST ***

"""

@pytest.fixture(autouse=True)

def mock_file(monkeypatch):

mock = mock_open(read_data=TEST_DATA)

monkeypatch.setattr("builtins.open", mock)

return mock

def test_get_content():

reader = TextReader()

content = reader.get_content("dummy_path.txt")

assert "This is a test document." in content

assert "It is only a test document." in content

def test_get_metadata():

reader = TextReader()

metadata = reader.get_metadata("dummy_path.txt")

assert metadata["title"] == "Test Document"

assert metadata["author"] == "Test Author"

assert metadata["id"] == 1234tests/readers/test_html_reader.py

PYTHON

import pytest

from unittest.mock import mock_open

from textanalysis_tool.readers.html_reader import HTMLReader

TEST_DATA = """

<head>

<meta name="dc.title" content="Test Document">

<meta name="dcterms.source" content="https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1234/1234-h/1234-h.htm">

<meta name="dc.creator" content="Test Author">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Test Document</h1>

<p>

This is a test document. It contains words.

It is only a test document.

</p>

</body>

"""

@pytest.fixture(autouse=True)

def mock_file(monkeypatch):

mock = mock_open(read_data=TEST_DATA)

monkeypatch.setattr("builtins.open", mock)

return mock

def test_get_content():

reader = HTMLReader()

content = reader.get_content("dummy_path.html")

assert "This is a test document." in content

assert "It is only a test document." in content

def test_get_metadata():

reader = HTMLReader()

metadata = reader.get_metadata("dummy_path.html")

assert metadata["title"] == "Test Document"

assert metadata["author"] == "Test Author"

assert metadata["id"] == 1234Challenge 2: Adding a New Reader

We have one last file type we haven’t added support for yet: Epub.

Create a new reader class for epub files called EpubReader

in a file called readers/epub_reader.py. You can use the

ebooklib package to read epub files. You can install it

with pip:

You can refer to the package documentation here

To get the metadata from an epub file, you can use the

get_metadata method of the EpubBook class.

Project Gutenberg uses the “Dublin Core” metadata standard, so the

namespace is “DC”.

Here’s an example of how to get the title:

The get_metadata method returns a list of tuples, where

the first element is the value and the second element is the attributes,

so we need to access the first element of the first tuple to get the

actual title.

The other metadata fields we need are “creator” (author) and “source” (id).

To get the content from an epub file, we can iterate over all of the

“items” in the book that are a document, then use

BeautifulSoup to extract the text from the HTML

content.

PYTHON

import re

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import ebooklib

from textanalysis_tool.readers.base_reader import BaseReader

class EPUBReader(BaseReader):

SOURCE_URL_PATTERN = "https://www.gutenberg.org/files/([0-9]+)/[0-9]+-h/[0-9]+-h.htm"

def read(self, filepath: str) -> ebooklib.epub.EpubBook:

book = ebooklib.epub.read_epub(filepath)

if not book:

raise ValueError("The file could not be parsed as EPUB.")

return book

def get_content(self, filepath):

book = self.read(filepath)

text = ""

for section in book.get_items_of_type(ebooklib.ITEM_DOCUMENT):

content = section.get_content()

soup = BeautifulSoup(content, features="html.parser")

text += soup.get_text()

return text

def get_metadata(self, filepath) -> dict:

book = self.read(filepath)

source_url = book.get_metadata(namespace="DC", name="source")[0][0]

extracted_id = re.search(self.SOURCE_URL_PATTERN, source_url, re.DOTALL).group(1)

metadata = {

"title": book.get_metadata(namespace="DC", name="title")[0][0],

"author": book.get_metadata(namespace="DC", name="creator")[0][0],

"extracted_id": int(extracted_id) if extracted_id else None,

}

return metadata- Composition allows us to build complex functionality by combining several smaller, simpler classes

- Composition promotes separation of concerns, reusability, flexibility, and maintainability

- By using abstract base classes, we can define interfaces that subclasses must implement, allowing for flexibility in our code design