Virtual Environments

Last updated on 2025-09-18 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is a Virtual Environment? / Why use a Virtual Environment?

- How do I create a Virtual Environment?

Objectives

- Create a new virtual environment using

uv - Push our new project to a GitHub repository.

What is a Virtual Environment?

A virtual environment is an isolated workspace where you can install python packages and run python code without worrying about affecting the tools, executables, and packages installed in either the global python environment or in other projects.

What is the difference between a “package manager” and a “virtual environment”?

A package manager helps automate the process of installing, upgrading, and removing software packages. Each package is usually built on top of several other packages, and rely on the methods and objects provided. However as projects are upgraded and changed over time, the available methods and objects can change. A package manager solves the complex “dependency web” created by the packages you would like to install and finds the version of all required packages that meets your needs.

Why Would I use a Virtual Environment?

If you are only ever working on your own projects, or on scripts for a single project, it’s absolutely fine to never worry about virtual environments. But as soon as you start creating new projects working on code written by other people, it becomes incredibly important to know that the code that you are running is running on the exact same versions of libraries.

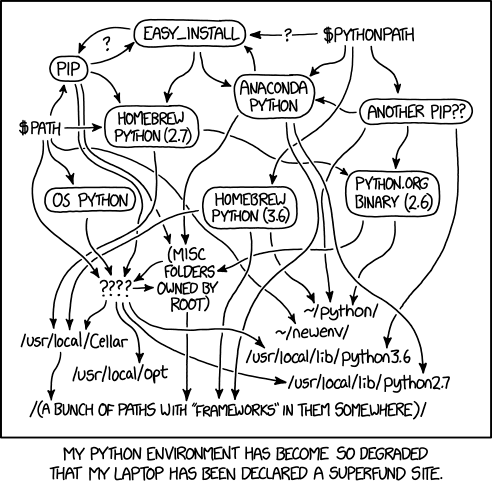

In the past, it was notoriously difficult to manage environments with python:

There have been a number of attempts to create a “one size fits all” approach to virtual environments and dependency management:

- venv

- virtualenv

- conda

- pipenv

- pyenv

- poetry

We’re going to use uv for the purposes of this workshop. UV is a another tool that promises to slot in to the needs of environment and dependency management, however there are a few key elements that set it apart:

- It is written in Rust, which gives it a significant speed improvement over pip and conda.

- It works with the

pyproject.tomlanduv.lockfiles, which allow for human and computer readable project files. - It can install and manage it’s own python versions.

- It works as a drop-in replacement for pip, eliminating the need to learn new commands.

Creating a project with UV

Before the workshop, you should have had a chance to install and check that your python and uv executables were working. If you have not yet had a chance to do this, please refer to the setup page for this workshop.

We’re going to start with a totally blank project, so let’s create a

directory called “textanalysis-tool”. Navigate to this directory in your

command line. Let’s quickly make sure we have UV installed and working

by typing uv --version. You should see something like the

following (the exact version number might be different):

We can start off with a new project with UV by running the command

uv init. This will automatically create a couple files for

us:

We can see that there are a few files created by this command:

-

.python-version: This file is used to optionally specify the Python version for the project. -

main.py: This is the main Python script for the project. -

pyproject.toml: This file is used to manage project dependencies and settings. -

README.md: This file contains human written information about the project. -

.gitignore: (Depending on your version of uv) This file specifies files and directories that should be ignored by git.

If we take a look at the pyproject.toml file, we can see

that it contains some basic information about our project in a fairly

readable format:

TOML

[project]

name = "textanalysis-tool-{my-name}"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Add your description here"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.13"

dependencies = []The requires-python field may vary depending on the

exact version of python you’re working with.

Make sure to change {my-name} in the name

field to something unique, such as your GitHub username. This is

important later when we upload our package to TestPyPI, as package names

must be unique.

Creating a Virtual Environment

To create a virtual environment with UV, we can use the

uv venv command. This will create a new virtual environment

in a directory called .venv within our project folder.

Before we activate our environment, let’s quickly check the location of the current python executable you are using is by starting a python interpreter and running the following commands:

Depending on your operating system, you may need to type

python3 instead of python to start the

interpreter.

You can type exit to leave the python interpreter

You should see the path to the location of the python executable on

your machine. Now let’s activate our environment. The exact command will

depend on your operating system, but if you look above the python code

to the output of the uv venv command, you should see the

correct command.

If this command works properly, you should see that before your prompt is now some text in parenthesis:

(textanalysis-tool) D:\Documents\Projects\textanalysis-tool>Let’s start up the python interpreter again and check the location of our executable:

What you should now see is that the executable is located in the .venv/Scripts directory of our project:

(textanalysis-tool) D:\Documents\Projects\textanalysis-tool>python

Python 3.13.7 (tags/v3.13.7:bcee1c3, Aug 14 2025, 14:15:11) [MSC v.1944 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import sys

>>> sys.executable

'D:\\Documents\\Projects\\textanalysis-tool\\.venv\\Scripts\\python.exe'Exit out of the interpreter and deactivate the virtual environment

with deactivate.

Git Commit and Pushing to our Repository

Some versions of uv will automatically create a

.gitignore file when you run uv init. If you

don’t see one in your project folder, you can create one manually.

We also want to create another file called .gitignore,

to control which files are added to our git repository. It’s generally a

good idea to create this file early on, and update it whenever you

notice files or folders you want to explicitly prevent from being added

to the repository.

We can create a gitignore from the command line with

type nul > .gitignore (Windows), or

touch .gitignore (Mac/Linux). There are several pre-written

gitignores that we can optionally use, but for this project we’ll

maintain our own. Open up the file and add the following lines to

it:

__pycache__/

dist/

*.egg-info/

scratch/A commonly used gitignore is the Python.gitignore maintained by GitHub. You can find it here.

Next, let’s set up a repository on GitHub to store our code. We’ll make an entirely blank repository, with the same name as our project: “textanalysis-tool”.

We’re creating the files on our local machine first, then the remote repository. There’s no reason you can’t go the other way around, creating the remote repository then cloning it to your local machine.

First, we’ll initialize a git repository locally, making an initial commit with the files that uv generated:

git init

git add .gitignore .python-version README.md main.py pyproject.toml

git commit -m "Initial commit"Then we’ll follow the directions for creating a new repository:

git remote add origin https://github.com/{username}/textanalysis-tool.git

git branch -M main

git push -u origin mainWe are using https for our remote URL, but you can also

use ssh if you have that set up.

If all goes well, we’ll see our code appear in the new repository:

And with that, we’re ready to start writing our tool!

Challenge 1: Adding a Package Dependency

Now that we have our project set up, let’s add a project dependency.

Later on in the workshop, we’ll be parsing HTML documents, so let’s add

the beautifulsoup4 package to our project.

Try the following command

uv add beautifulsoup4Take a look at the pyproject.toml and

uv.lock files. What changed? What is the purpose of each

file?

What is the difference between the command

uv add beautifulsoup4 and

uv pip install beautifulsoup4?

The pyproject.toml file is a human readable file that

contains the list of packages that our project depends on. The

uv.lock file is a machine readable file that contains the

exact versions of all packages that were installed, including any

dependencies of the packages we explicitly installed.

uv add will add the package to the

pyproject.toml file, and install the package into our

virtual environment. uv pip install will install the

package into our virtual environment, but will not add it to the

pyproject.toml file.

- Setting up a virtual environment is useful for managing project dependencies.

- Using

uvsimplifies the process of creating and managing virtual environments. - There are several options other than

uvfor managing virtual environments, such asvenvandconda. - It’s important to version control your project from the start,

including a

.gitignorefile.